Wildwood by Helen Scott Taylor

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

More than fifty years ago I read The Weirdstone of Brisingamen by Alan Garner, and went on to read his other children's books, and wished he'd written more, or that someone else would, and now someone else has. This book is certainly in the same genre, though see below for a discussion of what exactly that genre is. The protagonist, Todd Hunter, is a teenager, but the story had more in common with Alan Garner's children's novels than his teenage ones like The Owl Service and Red Shift.

Todd Hunter's father has been missing for five years, and he doesn't get on well with his mother's new boyfriend, so when the rest of the family go to spend their holidays with the mother's boyfriend's family in France, Todd goes to stay with his paternal grandfather in a small Cornish fishing village. There he hopes to learn more about his father, and even perhaps to learn something about the mystery of his disappearance.

Todd's grandfather John runs a grocery shop, in which Todd helps out occasionally. There are few young people of his own age in the village. He meets a rather unpleasant boy of about his age, Andrew Bishop, who, like Todd, doesn't get on with his stepfather. But soon after Todd's arrival, Andrew disappears, and Todd discovers his body at the foot of a cliff. The police rule his death accidental, but Todd suspects that he was murdered by his stepfather, perhaps reflecting his dislike of his own stepfather, and decides to investigate Andrew's death on his own. He also meets a teenage girl, Marigold, whom he finds quite attractive, but is rather wary of, because he discovers that her mother is reputed to be a witch.

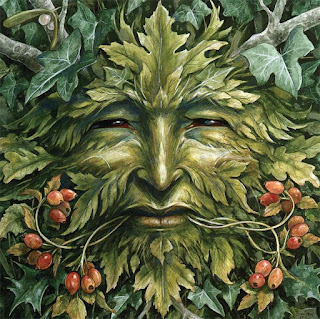

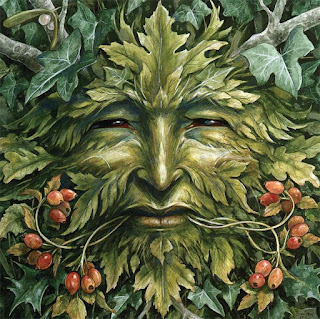

Before he has been in the village a week, Todd find himself investigating several mysteries -- his father's disappearance, Andrew's death, and a cult of the

Green Man, which several people seem to be involved in. He also befriends an artist, Shaun, and his pet dog Picasso. Shaun, like Todd, is not originally from the village, and sometimes Todd finds his outsider's point of view refreshing. The longer he spends there, the more he feels he wants to get out, and the more he learns about the place and its history, and the activities of its present inhabitants, who seem determined to keep him there forever, the more he wants to leave.

I found it an exciting book, full of unexpected plot twists, though towards the end some of them became too inconsistent and inexplicable, with some characters shifting a bit too rapidly back and forth between loyalty and betrayal to be convincing.

The book seems to be only available on Smashwords, and if you like juvenile books with adventure, mystery, ghosts and a touch of supernatural magic, it's definitely worth a read. You can see a fuller description on the Smashwords site here.

As I said at the beginning, I thought this book would appeal to people who liked Alan Garner's children's books. I would say that this one is roughly in the same genre. But what genre is that, and how does one describe it? On Smashwords, Wildwood is described as "Y/A Paranormal" and I don't think I've ever seen Alan Garner's books described as "paranormal" before. I have written a couple of children's books in the same genre, and described them as "children's adventure/fantasy", though one of my reviewers did classify one of them as "paranormal-fantasy". In adult books with similar themes, the novels of Charles Williams have been described as "supernatural thrillers", but never, as far as I am aware, as "paranormal".

The problem here seems to be that for many people "fantasy" implies that the story is set in a location out of this world, and these stories are not (with the partial exception of Alan Garner's Elidor). The problem with "paranormal", for me at least, is that it evokes images of movies like Ghostbusters, and rather misguided attempts to measure spiritual phenomena with material instruments, like using a photographic light meter to measure the light from the transfiguration of Jesus, or parlour tricks like Uri Geller bending teaspoons.

Anyway, whatever you want to call this genre, I like it, and am glad to see other people writing it, and hope to write some more in it myself. Another book in the same genre is The Dark is Rising by Susan Cooper, which I had read a few months before reading this one. As I explained in my review of The Dark is Rising, one of the things I didn't like much about that book was that the protagonist was not really human, but had superpowers, and there is a hint of that in Wildwood, where we are frequently told that Todd Hunter has a "hunter's instinct" that makes him different from everyone else. It's one of the reasons I gave the book four stars rather than five, not because it makes it a bad book or anything, but the star rating is subjective, how much a particular reader likes a book, and I don't much like books where the protagonist has superpowers, even when, as in the case of Todd Hunter, they so often fail at a critical moment.

View all my reviews