The Plumed Serpent by D.H. Lawrence

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

Meh.

A long rambling waffling book about two men who found a neopagan religion in Mexico and an Irishwoman who marries one of them, and spends half the book trying to decide whether to marry him, and the other half wondering whether she ought to have done so.

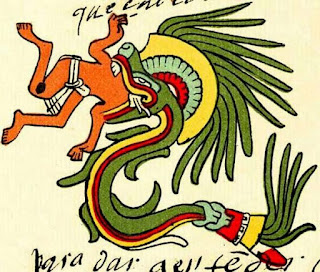

Kate Leslie, a wealthy middle-aged Irish tourist on holiday in Mexico, meets a Mexican general, and his friend, a wealthy landowner, and goes to visit their part of the country, where she extends her stay indefinitely. She helps to rescue the landowner from some would-be assassins, and is asked to marry the general and join the pantheon of their neopagan religion, in which the landowner is Quetzalcoatl, the eponymous plumed serpent deity, while the general is Huitzilopochtli. Kate is ambivalent about her assigned role as divine consort to Huitzilopochtli, and remains so to the end.

So why, if it was so long-winded, preachy and dull, did I bother to buy and read this book?

The answer goes back to my youth in the early to mid-1960s, when I was a student at the University of Natal in Pietermaritzburg. The university English department had made its own literary neopagan religion, in which D.H. Lawrence was the chief deity, with a supporting cast of Joseph Conrad, Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, and Shakespeare, and their very own incarnate Huitzilopochtli, H.W.D. Manson, the greatest playwright since Shakespeare. I didn't earn any brownie points with my tuto, Christina van Heyningen, when I said that I liked Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter and Eugene Ionesco better than Manson's The Counsellors.

But I still thought I ought to read at least one D.H. Lawrence novel to see what all the fuss had been about, and I picked this one because it was exotic, at least to Lawrence, and wasn't full of coal mines, the English Midlands, and the early 20th-century working class.

As Kate is indecisive throughout the book, Lawrence (or at least his characters) can't make up their minds and they often expound inconsistent ideas, as does Lawrence when giving his omniscient narrator's opinion. The white and the dark-skinned races should never meet, and should have their own religions, their own cultures, their own way of life -- "own affairs" as the old apartheid ideology used to put it. But this will eventually lead to a new man, with new blood and all will be one. Oh yes, there's lot about blood in this story. It's a very bloody book, starting from the opening bullfight scene and drifting off into the obscure philosophy about how white blood and black blood should never mix, but will eventually become one, or something.

White blood is superior to dark blood, but the time of supremacy of dark blood is coming. And aristocratic blood is better than the blood of peons. Lawrence appears to believe in a kind of Nazi uebermensch:

The star which is a man's innermost clue, which rules the power of the blood on the one hand and the power of the spirit on the other. For this, the only thing which is supreme above all power in a man, and at the same time, is power; which far transcends knowledge, the strange star between the sky and the waters of the first cosmos; this is man's divinity. And some men are not divine at all. They have only faculties. They are slaves, or they should be slaves.Read it quickly, and it can sound profound. Read it paying more attention, and its profundities are as empty as those of the Unman in C.S. Lewis's Perelandra, and the only bit that actually says anything, other than meaningless symbols and abstractions, is the last sentence: Lawrence believes that some men are born slaves and others are born masters, and that's as it should be. It was probably passages like this that led some critics to say that Lawrence was being fascist here. But half the book is like this -- boring pretentious pseudo-spiritual twaddle.

No comments:

Post a Comment