But one of our regular members was taken ill, and another died, and so it looked as though our fourth anniversary gathering today might be the last. So we had a "Meeting for Business", as the Quakers say, to discuss whether we should continue, and decided that we would. But we also thought that there must be more people in the Great City of Tshwane who liked the Oxford Inklings and their writings, and might like to chat about them, or the kind of things they talked about, over a cup of coffee. So if you are reading this and know anyone like that, please tell them about us.

This time we discussed quite an eclectic range of books, yet there also seemed to be a common theme. I had read one called The Horse Road (review here) about a horse-mad girl in Central Asia in the first century BC whose mother would not allow her to keep slaves as she herself had been a slave. They were nomadic horse breeders, and we talked about the Khoi of the Western Cape, who were originally nomadic pastoralists and moved around.

Janneke Weidema had been reading a book about the Sovietising of outer Mongolia, which she thought had similarities to the enclosure movement in England, perhaps related to a verse:

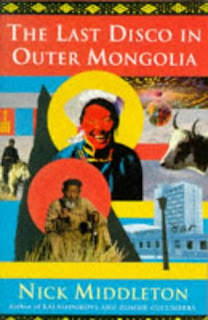

The law locks up the man or womanThe Mongols too were nomadic pastoralists and the Soviet Russians had tried to force them to settle on collective farms and grow crops. I had not long ago read a book that dealt with the other end of that process, The last disco in Outer Mongolia.

Who steals the goose from off the common

But leaves the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from the goose.

Nick Middleton visited Mongolia in 1987 and in 1990, shortly before and shortly after the switch from Communist bureaucracy to a more liberal and democratic society. As a geographer on his first

visit he was working on hydrography, on his second he was planning for ecotourism. He catches a society in transition from one mode to another.

So Janneke had read a book relating to the beginning of the Bolshevik period, and I read read a couple relating to the end of it. But I had also read one relating to the middle of it, and that tied up a lot of loose ends. The book relating to the middle of it was Journey into Russia by Laurens van der Post -- see my review here, especially the last couple of paragraphs.

There was a common thread running through all of them -- in both communism and capitalism it was the common people who were being screwed by the bureaucrats, the apparatchiks, the managers, the MBAs. Whether it's the goose on the common, the pastures of the Khoi in the Western Cape or the Mongolian nomads, or the people who are being called on to pay ever more for electricity because of the follies of Eskom and the modern equivalent of enclosures -- land reform in South Africa. It's basically the same at root.

Van der Post put his finger on it when he wrote about the state and the collective farms of the USSR:

The revolution had worked a confidence trick on them all. They had revolted in order to have the land to themselves. But no sooner was the revolution consolidated than a far more inflexible landlord, the State, had taken it away from them again in the name of collectivization. And, judging by the show pieces I saw, there were few farmers in charge of farms. Party secretaries, accountants and factory foremen were the types one usually found in positions of command.Back in the old days, when Eskom was Escom, the ESC, the Electricity Supply Commission, it was mainly run by engineers. In those days, the 1960s and 1970s, most electricity was generated from coal, and rather than transporting coal to the power stations, they built the power stations where the coal was, in what is now the Highveld of Mpumalanga, which came to be called "Kragveld" for that reason.

Then in the 1980s came the mania for privatisation (the Reagan/Thatcher years). Escom was privatised and became Eskom, a State-Owned Enterprise (SOE), though since it was still owned by the State one could say it was semi-privatised. But the coal mines that the power stations were built on were fully privatised -- some of them ended up in the hands of the Guptas -- and they found it was more profitable to sell the coal overseas than to sell it to Eskom, and so Eskom had to buy coal where they could, often of the wrong quality and at vastly inflated prices. And the privatised Eskom was run by managers, by bureaucrats, not by engineers, just like the Soviet state and collective farms that Van der Post wrote about.

And so, as George Orwell wrote at the end of his fable Animal Farm, the ordinary animals looked from men to pigs, and from pigs to men, from capitalists to communists and from communists to capitalists, and could no longer tell the difference.