one of the books I finished last night is J. Milton Yinger's Countercultures: The Promise and Peril of a World Turned Upside Down (New York: The Free Press, 1982). In his chapter on symbolic countercultures he includes discussion on rituals of opposition and how these serve or function as countercultures. In this section he discusses the belief in "inverted beings" among the Lugbara in what is now known as Uganda. He states that these beings "behaved in ways 'the opposite of the ways expected of normal socialized persons in Lugbara society today.'"

The description "inverted beings" could also apply, though in different ways to the holy fools found in the Chrsitian world. As Jim Forest puts it

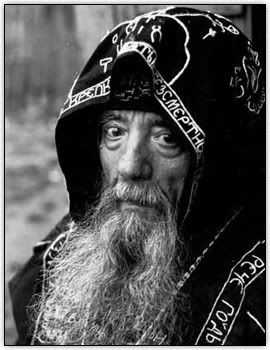

While there is much variety among them, holy fools are in every case ascetic Christians living outside the borders of conventional social behavior -- people who in most parts of the developed world would be locked away in asylums or ignored until the elements silenced them.

Karen M. Staller, the author of a book on Runaways, describes in an interview how the 1960s counterculture influenced American society and worldwide youth culture

Q: You argue the counterculture was influential in this discussion. How so?

KS: I make at least three arguments in this regard. First, by using the New York Times as a source of evidence, I trace the construction of "runaway" stories over an eighteen-year period. In the early 1960s, running away was characterized as a private family matter of little public consequence, but by the mid-1970s it was being typified by young teenage prostitutes. This shift is traceable to 1966-67, when runaway accounts commingled with reports on the hippie counterculture. The "safe runaway adventurer story" construction could not survive, and what emerged in the aftermath of the "hippie" phenomena was a new conceptualization of the typical runaway as a much more troubled, street-based child.

Second, I argue that writers of the Beat movement were providing an alternative (and much more hip) version of "dropping out" for a generation of Baby Boomers who were reading works like Kerouac's On the Road (for example, I use the life histories of two Beat "muses," Herbert Huncke and Neal Cassady). This version of "running away" stood in sharp contrast with the Establishment's interpretation. Arguably, a second generation of counterculturists, calling themselves Diggers, picked up on these ideas and created youth communities that embodied much of the "beat" philosophy. Runaways were attracted to these ideas and to the lifestyle being enacted in counterculture communities such as Haight-Ashbury.

Third, during the mid-1960s the Diggers were engaged in a cultural critique in which they attempted to "enact Free." Their goal was to create a true counterculture that would sustain a community of like-minded social activists free of the social, cultural, moral, and economic constraints of mainstream society. In the process of performing "Free," Diggers provided free crash pads, free clinics, free food, a free store, and telephone help lines (hence earning them such much-detested labels from mainstream journalists as "psychedelic" social workers, "mod" monks, and "hip" charity workers). Both the messages emanating from these communities about love, peace, and alternative families, and the concrete services being provided, were attractive to younger runaway children. In 1967, as the media, acid rock, and pop music groups of the day promoted a so-called "Summer of Love" in San Francisco, Diggers called on the local community for help in caring for the younger children. The community responded by opening Huckleberry House, the first of what would become a nationwide movement of alternative and radical service providers that sheltered runaway children. The shelters looked quite a bit like the Digger crash pads and incorporated many counterculture values.

Towards the end of the hippie period the film Brother Sun, Sister Moon was released. It showed the life of Francis of Assissi, incorporating the hippie values of the dropout culture. And the early Franciscan movement was certainly countercultural in its own time, in a way that appealed to those involved in or at least sympathetic with the counterculture. In 1960 an Anglican monk, Brother Roger of the Community of the Resurrection, wrote an article with the title God's cool cat: How Beat were the Franciscans and how Franciscan are the Beats? anticipating Zefirelli by nearly 15 years.

Towards the end of the hippie period the film Brother Sun, Sister Moon was released. It showed the life of Francis of Assissi, incorporating the hippie values of the dropout culture. And the early Franciscan movement was certainly countercultural in its own time, in a way that appealed to those involved in or at least sympathetic with the counterculture. In 1960 an Anglican monk, Brother Roger of the Community of the Resurrection, wrote an article with the title God's cool cat: How Beat were the Franciscans and how Franciscan are the Beats? anticipating Zefirelli by nearly 15 years.In the early 1970s, however, the theoretical possibilities were taking practical form. Jesus freaks like the Children of God were spreading to cities throughout the world distributing their publication New Nation News, and urging people to see Brother Sun, Sister Moon. They lived in hippie communes, which they called "colonies", a term also used by the early Christian communities. Here, for anyone who wanted to see, was the new monasticism. Here were the "inverted beings" trying to turn the world upside down, or, from their point of view, right side up.

Unfortunately, as often happens with idealistic movements, things went sour. In the case of the Children of God the leader, Dave Berg, who called himself Moses David or just Mo, became increasingly erratic and authoritarian. In later issues of New Nation News it became apparent that "Mo" was trying to draw people to himself rather than to Jesus, and the pages of the magazine became increasingly filled with sexual innuendo, for which Dave Berg coined the term "flirty fishing". But that was far from the vision of the Durban colony of the Children of God in 1974, who preached and lived the love of God and urged people to see a film about the life of Francis of Assissi.

I believe that one of the things that went wrong with the "new monasticism" of the Children of God was that it was disconnected from the old monasticism. The Orthodox "fools for Christ" are inverted beings, and very often their behaviour, by the standards of respectable society, is quite bizarre. The Greek word for them, sali, is the root of the English word silly, and a silly fool is a blessed fool, one who has been touched by God.

I believe that one of the things that went wrong with the "new monasticism" of the Children of God was that it was disconnected from the old monasticism. The Orthodox "fools for Christ" are inverted beings, and very often their behaviour, by the standards of respectable society, is quite bizarre. The Greek word for them, sali, is the root of the English word silly, and a silly fool is a blessed fool, one who has been touched by God.Also in the 1970s an American, Eugene Rose, became an Orthodox monk. He had studied at the American Institute of Asian Studies in San Francisco where he met Gary Snyder, one of the inspirers of the Beats, immortalised in Jack Kerouac's novel The Dharma bums as Japhy Ryder. Eugene Rose took the monastic name Seraphim, and sought to establish an American version of traditional Orthodox monasticism. In the 1990s the example of Fr Seraphim Rose inspired a new generation of youth to distribute a revolutionary Christian zine, Death to the world. It was the same size and format as New Nation News, but it had its roots in 20 centuries of monastic wisdom. "Death to the world is a zine to inspire Truth-seeking and soul searching amidst the modern age of nihilism and despair, promoting the ancient principles of the last true rebellion: to be dead to this world and alive to the other world." It published testimonies of the new generation of "punx 2 monks", and its story was told in a book Youth of the Apocalypse.

It is perhaps a coincidence that the traditional dress and external appearance of monks resembled that adopted by many in the counterculture of the 1960s -- long hair in pony tails and beards for the male monastics. But the internal rebellion has remained the same through the ages: rejection of the dog-eats-dog consumer society.

It is perhaps a coincidence that the traditional dress and external appearance of monks resembled that adopted by many in the counterculture of the 1960s -- long hair in pony tails and beards for the male monastics. But the internal rebellion has remained the same through the ages: rejection of the dog-eats-dog consumer society.One problem is that countercultures keep getting coopted by mainstream cultures. The Beats of the 1950s and the hippies of the 1960s had various visions of alternative lifestyles. But it wasn't long before banks were offering "lifestyle banking", and the lifestyle they promoted in their advertising was one of conspicuous consumption: a yacht, a swimming pool, a fancy car -- a far cry indeed from the simple lifestyle advocated by the counterculture. But even the most imaginative copywriter would be hard put to come up with "lifestyle banking" for monks.

The Jesus freaks of the late 1960s and early 1970s promoted "revolution for Jesus", but it wasn't long before the slogans and symbols of the revolution were being coopted by young fogeys in suits who ran middle-class youth groups in middle-class suburban churches, and promoted a new line of sanitised Jesus kitsch like patches to put on your pre-faded, pre-shrunk, pre-torn jeans.

The last true rebellion was also the first. There may be a need for a new monasticism, but apart from the old, it will easily be coopted by the world. No mater how the world's fashions change, monks somehow always look, and are, countercultural.

8 comments:

There is a lot of truth in what you write. For Christianity (of some form) to survive, we need to become a subversive counterculture. We need to be "resident aliens". I'm not sure what this will look like, but I think the basis can be found in Scripture - especially Acts.

Good post.

When we become Christians, we become resident aliens, squatters, parishioners, sojourners.

Steve

Among those Protestants who see themselves as Emerging Church there are some who talk about a new monasticism. It seems to involve a nostalgic and selective glance at Celtic Christianity, and at the Rule of Benedict, or occasionally elements that are in the Orthodox churches.

Some Emerging Church people have blogged about how they have formed new monastic orders, covenanting to be like Christ in postmodernity, and following some elements say of the Benedictine rule.

However, it seems to me that these discourses are not seriously grounded in a proper understanding of monasticism. That is, there seems to me be some naive impressions or romanticised ideas about monasticism.

It is true that we often like to glimpse selectively at the past and that we take to the past our current questions as we want to resolve our current dilemmas. However, romanticised notions do tend to obscure the past, and selected morsels that are mixed and matched create a hybrid that is only tangentially related to the original sources (in this case the various established monastic orders, traditions etc).

The desire seems to be to find a spirituality that works and is suited to being a high-tech middle class westerner, with the enchanting appeal of things like candles, meditations, Taize material, labyrinths, lectio divina and so on.

However the full implications of monastic spiritual life is clearly not grasped if the blogs are to be taken as a guide to what people really know and practice.

For example, I see romantic notions about Celtic Christianity that reads into the past a portrait of what people would love to experience today -- connection with one another in community, a deep appreciation for creation, a vibrant spiritual life of devotions and so on.

I also see the Benedictine Rule being read and appropriated in a rather selective way and the historical-social-religious context in which it was conceived is not understood.

As regards monasticism generally, the perfection of the saints, is a point that is not acknowledged or articulated in these new discourses (even if by way of saying "no thanks").

I feel that these keen and passionate Emerging Church people would really find it difficult to reconcile monasticism with what they have received in their Protestant backgrounds. It follows that integrating monasticism, whether it be the Orthodox or Catholic traditions, would be theologically hard to integrate given the assumptions that most Protestants work with, and particularly the inherited spiritual discourses of evangelical, charismatic and Pentecostal networks.

Even those in EC who seem to be extricating themselves from those inherited sources still have a long way to go before their neo-monasticism can truly be deemed to be monasticism.

I think that the desire for what is imagined to be monasticism (or the best bits selected from it) does point to serious omissions in contemporary Western Christian circles generally that these folk genuinely want to overcome.

Unless there is some theological depth and maturity brought to the table, the ever-present problem is then slipping into precisely the same problems that beset the Jesus Movement, and as was seen in the aberrations of Moses David's teachings. In this respect the old adage of not learning from the lessons of history (one is then doomed to repeat them) comes to mind.

Phil,

Thanks for your thoughtful and thought-provoking response.

Yes, I'm sure you are right -- there's a lot of romantic wishful thinking involved in neomonasticism, and if it is built on nothing more than idealism, it is bound to fail.

I was myself involved in a community of sorts back in the 1970s, and know that it's not easy. I was pleasantly surprised to see that the Children of God had succeeded in some areas where we had failed, but of course they had their failures too,

And one problem is the Western Protestant emphasis on the "word". But you can't learn everything that you need to learn merely by reading about it. Reading the Rule of St Benedict is no substitute for novitiate in the order. And on the Orthodox side, people are advised not to read the Philokalia (a collection of texts for the spiritual guidance of monks) without the guidance of a spiritual father. Yet people still do read it (yes I did too!) unguided, and then sometimes suffer from the deluision that, having read it, or bits of it, they are in a position to give spiritual guidance to others.

I think there is a problem with the term itself -- neomonasticism or "new monasticism", which implies that this is something that supersedes the old monasticism, but much of the point of what I wrote is that it doesn't.

I think something like neomonasticism is needed, but it is not monastic, or a substitute for monasticism. At best it is ancillary to monasticism. It might be possible, and even desirable, to encourage various forms of community life under a rule of some sort, but I think it would stand the best chance of success if such a community were rel;ated to spiritual fathers (or mothers) who were real monks. It might be better to call such communities semi-monastic, rather than neomonastic.

What does the Emerging Church have to do with monasticism? Or, why does 'new monasticism' locate itself within EC?

I take Phil's point that contemporary fascination with things monastic is a western fad. Nevertheless, non-classical monasticism has interpreted Church meaningfully to sectors of society quite sick of vanilla.

My questions are:

- can neo-monasticism emerge in South Africa?

- would we recognise it in EC categories?

- would it be contemplative and missional, or are these terms mutually exclusive?

Carl,

I think monasticism and neomonasticism are among the things that are "emerging" or reemerging in 21st century Christianity. Whether that makes them part of the "emerging church conversation" is perhaps a moot point.

The Children of God emerged in South Africa in the early 1970s, and were decidedly missional and less contemplative. But traditional monasticism seems to have been both, at least to the extent that for 1000 years, between 500 and 1500, most Christian mission was monastic.

I concur that (new) monasticism is more part of an emerging conversation than of the Emerging Church. But Phil's contention that the phenomenon resonates with a western "high-tech middle class" has significant implications for African Christianity.

Can a new monasticism take root in African soil? If so, with what justification? What continuities will it share with traditional monasticism, and what will be its points of departure?

Carl,

Phil's contention was that the new monasticism had a kind of romantic appeal to the Western high tech middle class, but that this was not enough to make it succeed. My point was that it is more likely to succeed if it has links to traditional monasticism of the desert fathetrs, which is still found in Ehypt and Ehtiopia.

A semi-traditional monasticism took off among Anglicans in rural Zululand, largely as a result of a charismatic renewal movment. From 1966 to 1976 the Community of the Holy Name grew from 3 to over 40 members. I haven't been in contact with them recently, but I know some of them are now working in johannesburg.

Post a Comment